What is more thrilling than spending five hours with like minded gardeners and naturalists on a cold January day? Seeing a room full of people that have embraced native Texas plants, feeling their enthusiasm about restoring our prairie ecosystem and knowing that so many have joined the revolution and are planting native plants.

“Just dig it: Practical ideas for adding native plants to your yard” was hosted by Friends of LLELA – Lake Lewisville Environmental Learning Area – earlier this month, and featured four wonderful speakers each discussing different aspects of gardening with native prairie plants.

Now before I go on, I simply must share a photograph of my son, taken during a nature class at LLELA, many moons ago. My son is now a college graduate and, thankfully, still loves the outdoors. I have faith that this generation of kids will take the baton and carry on protecting and restoring important ecosystems around the globe.

Before we bought our home nearly thirty years ago, I knew “how” I wanted to garden – passionately, organically, naturally. My garden has evolved a lot over the decades, but those three things have never changed. I have always loved our native plants and – once upon a time – worked at an organic garden center that was one of the few (at that time) in the Dallas-Fort Worth metroplex that offered native plants. Yes, I once had over 150 antique and heirloom roses. But I also incorporated a variety of native plants. Yes, my garden now grows fruits and vegetables. But I still love native plants and try to squeeze in as many as possible. I am not a purist. I don’t personally believe that the average home garden has to be 100 percent native plants to be beneficial. I believe that every bit of habitat we can provide for wildlife is important. I believe that one can have entirely native prairie plants or a mix of native and non-native plants. Every action to preserve or restore habitat is important, no matter how small.

My garden is located in Denton county, just north of Dallas and Fort Worth, in the Cross Timbers and Prairies Ecological Region. This area was originally a combination of prairie and woodland, both of which provided a lush habitat for a large number of mammals and birds. Alas. As the song goes, “They paved paradise and put in a parking lot.” They also paved paradise and put in a major north-south interstate, I-35. One can drive from the southern border of Texas, past my garden just north of Dallas-Fort Worth, and all the way north to Minnesota. This central section of America is a major flight path for many migratory birds, as well as the now threated monarch butterfly. A road trip game of I Spy will net you a lot of billboards, fast food restaurants and acres of cultivated farmland, but very little wildlife habitat, either preserved or restored. This midsection of America is crucial for the survival of many birds and butterflies, which is why it is so important to plant native plants whenever possible – whether it be in the home garden, school garden or local nature center.

What can the average suburban or urban landowner do to counter all of that pavement and help restore lost habitat? Quite a bit, actually, just by reducing our lawn size and putting in a few native plants that provides much needed food and shelter. Or go a step or two further and put in a pocket prairie, a native prairie garden on less than an acre. This can be a small residential front yard or an entire backyard, whatever fits your style. In the ever-expanding sea of concrete throughout the central portion of America, every bit is important.

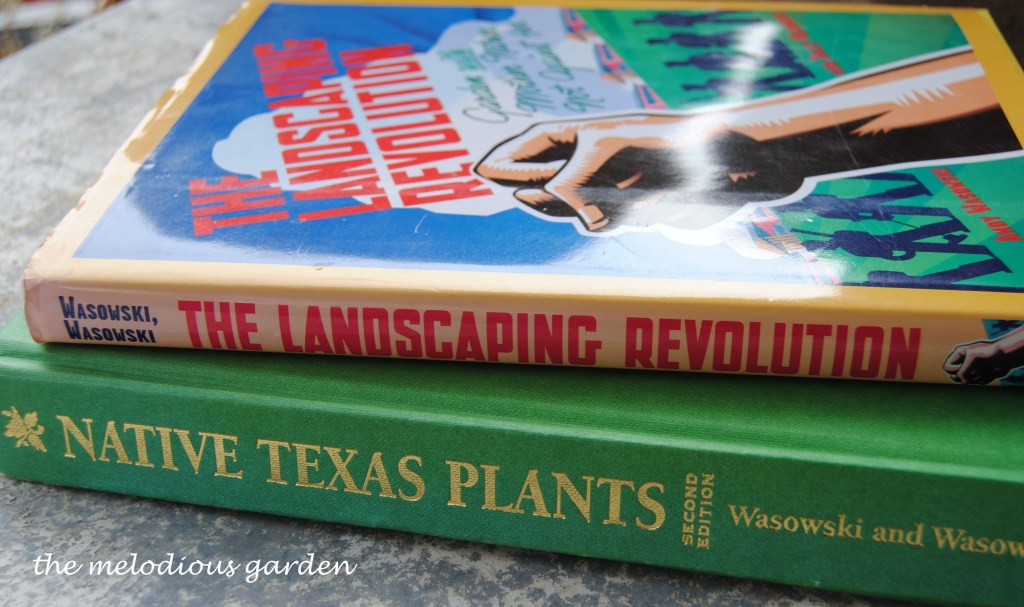

Andy and Sally Wasowski’s books on native plants and naturalistic gardening (shown above) were some of the first books that I bought after we purchased our home. They have been my inspiration and guide, both are books I go back to time and again. Some of the beautiful flowers I first learned about from Native Texas Plants are shown and briefly described below.

Penstemon tenuis, aka Gulf coast penstemon, shown below, is a great example of how fluid and ever changing native garden are. I no longer know where this was originally planted in my garden as it has popped up randomly here and there for many, many years. It has never been an aggressive reseeder, though any unwanted plants can easily be dug up and shared with fellow gardeners. This penstemon is extremely easy to grow and the lovely soft lavender color goes with many color schemes, if that is something that interests you. It is always covered with pollinators. This penstemon blooms early in the spring.

Echinacea, shown below, is another plant that moves about my garden and is always covered in pollinators. I leave the old flowerheads on the stalks over winter as songbirds love to feast on the seeds. In late winter I scatter any seeds that remain wherever I would like more to pop up.

Sisyrinchium, aka blue-eyed grass, shown below, is perhaps one of my favorite native plants. I love how dainty and crystal blue the flowers are. This is another early spring bloomer.

Malvaviscus drummondii, aka turk’s cap, shown below, is a highly adaptable plant, growing well in sun or shade and in wet or dry conditions. This is a favorite of hummingbirds and butterflies. It blooms through the heat of summer and up to the first hard freeze.

Callirhoe involucrata, aka winecup, shown below, rambles and scrambles about the garden. It grows from a tuber to form a rosette that then extends every which way. It blooms very early in the spring in my garden. Every few years, I dig out the older overgrown tubers and toss them in the compost pile, allowing the smaller tubers to grow and carry on.

Monarda fistulosa (shown below) is the native, wild growing bee balm. It is harder to find (often sold alongside herbs) but much more hardy than the newer hybridized variations.

A few years ago, I had both the wild bee balm and a hybridized variety growing side by side. The wild bee balm was covered in pollinators while the hybridized one was void of any insects. This was a great chance to witness why the wild varieties are favored by wildlife, as many hybridized plants are bred for color or size and often lack the amount of pollen and nectar that wild plants contain.

I had to save the best for last. My very favorite native plant of all time – Cephalanthus occidentalis, aka buttonbush, shown below. Yes, it does grow naturally along creeks and rivers, but it will grow nicely in a residential yard. Buttonbush can be pruned up to form a small scale tree, much as the non-native crepe myrtle. Buttonbush, however, has amazing, out of this world, blooming orbs!

Buttonbush, shown above and below, is always covered in pollinators when in bloom.

All photographs were taken in my suburban North Texas garden.